HISTORY

Extracts from : A Portuguese East Indiaman from the 1502–1503 Fleet of Vasco da Gama off Al Hallaniyah Island, Oman: an interim report, Mearns, D.L., Parham, D., and Frohlich, B, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology Vol. 45.2, © 2016 The Nautical Archaeology Society.

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery describes a period in European history when extensive overseas exploration by a handful of seaborne powers led to the rise of global trade in concert with the building of colonial empires. While the Spanish, French, Dutch, and English were all heavily involved in this economic and territorial expansion, it was the Portuguese, from their small coastal country fronting the Atlantic Ocean who were the first to venture beyond their shores to make important discoveries in the New World. Having discovered Madeira Island in 1418 and the Azores archipelago in 1427, Portuguese ships commanded by their most skilled explorers and navigators pushed further south reaching successively distant locations along the west coast of Africa.

These methodical explorations by the Portuguese were generally driven by their quest to conquer and exploit new lands whilst also searching for Christian allies (none more important than the legendary Prester John) who could help in their conflicts with the ‘Moors’ of North Africa. By the year 1488 Bartholomeu Dias had rounded the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and for the first time a European had entered the waters of the Indian Ocean. Only the nervousness of Dias’ crew prevented him from continuing his voyage all the way to India, which the Portuguese knew was a land rich in valuable spices and was their ultimate objective. Another decade was to pass before Vasco da Gama completed the voyage to India in 1498 (in a ship Dias reportedly help build) but it was Dias’ who first put the Portuguese at the doorstep to this exciting new land and to lands further east.

Fourth Portuguese Armada to India (1502-1503)

In 1502, four years after his discovery of the sea route to India earned him the titles Dom and Admiral of the Indies, Vasco da Gama was once again appointed Captain-Major by the Portuguese King Dom Manuel I for a voyage to India. Following the disastrous outcome of Pedro Cabral’s earlier (1500-1501) command of 13 ships, of which only six made it to the Malabar coast, da Gama was apparently a late replacement for Cabral of this 4th Portuguese voyage that was central to the prestige and military ambitions of Dom Manuel. The Portuguese King’s investment in the Indian Ocean had yet to turn a profit nor had it resulted in finding large numbers of friendly Christians in India that could be allies against the Mamluks of Egypt who controlled the spice trade through the Red Sea. In fact Cabral’s relations with the Zamorin of Calicut was decidedly unfriendly. Continuing da Gama’s policy of hostile trade Cabral’s fleet first seized a Muslim ship, which in turn precipitated a retaliatory attack by the enraged Muslim merchants on the newly established Portuguese feitoria (factory) in Calicut. Fifty-four Portuguese, including the feitor Aires Correia, were killed in the ensuing battle. Cabral’s reply to the heavy loss of his men and goods was to capture still more Muslim ships and then to bombard Calicut with his heavy guns killing as many as 500.

In replacing Cabral, Dom Manuel opted for a fleet that was full of military intent and family members of da Gama. Of the 20 ships, the largest Carreira da India fleet to date, five were commanded by present, or soon to be relations of da Gama, including: his uncles Vicente and Brás Sodré, a cousin Estêvão da Gama, a brother-in-law Alvaro de Ataíde, and a future brother-in-law Lopo Mendes de Vasconcelos. The main figure however, other than da Gama himself, was Vicente Sodré who was given his own regimento (instructions) by Dom Manuel and was to assume the role of Captain-Major if anything happened to his famous nephew. Sailing in the nau Esmeralda, Vicente led a separate five-ship squadron (three naus and two caravels) and together with his younger brother Brás engaged in some of the most brutal and notorious attacks on enemy ships they encountered off the coast of India.

After da Gama returned to Lisbon with the main part of the fleet in early 1503, the senior Sodré was instructed to patrol the waters off the southwest Indian coast. From this post he could protect the newly established Portuguese factories and their allies in Cochin and Cannanore from the inevitable Zamorin attacks, and still be able to capture Arab ships trading between the Red Sea and Kerala to fulfil the Royal regimento. However, Sodré ignored these instructions and instead sailed to the Gulf of Aden where his fleet captured and looted a number of Arab ships of their valuable cargoes. In conducting this high-seas piracy Sodré was abetted by his brother Brás in the nau São Pedro who led the brutal attacks, which spared no lives as every ship was burnt after being plundered. According to Pêro d’Ataíde, who was captain of the third nau, the Sodré brothers then kept the lion’s share of the stolen cargoes (pepper, sugar, clothing, rice, cloves) leading to dissension amongst the other commanders and crews.

In April of 1503, Sodré took his fleet to the Khuriya Muriya Islands off the southern coast of Oman to shelter from the southwest monsoon and to repair the hull of one of the caravels. They remained on the largest and only inhabited island (now known as Al Hallaniyah) for many weeks and enjoyed friendly relations with the indigenous Arab population, including bartering for food and provisions. In May the local fishermen warned the Portuguese of an impending dangerous wind from the north that would place their anchored ships at risk unless they moved to the leeward side of the island. Confidant that their iron anchors were strong enough to withstand the tempest the Sodré brothers, along with Pêro de Ataíde, kept their ships in the northern anchorage whilst the smaller caravels moved to a safe location on the other side of the island.

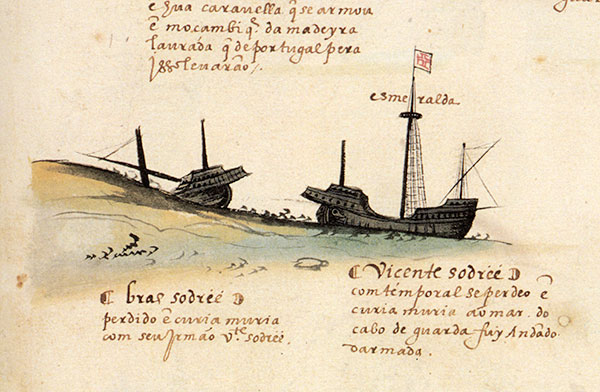

When the strong winds came, as the Arab fisherman had accurately predicted, they were sudden and furious and were accompanied by a powerful swell that tore the Sodré brothers’ ships from their moorings and drove them hard against the rocky shoreline smashing their wooden hulls and breaking their masts. An illustration made later for the pictorial chronicle Livro das Armadas dramatically captures the demise of the two naus. Whilst most men on the São Pedro survived by scrambling across her fallen mast and rigging onto land it was reported that everyone from the Esmeralda, including Vicente Sodré, perished in the deeper waters of the bay. Although Brás initially survived the wrecking of his ship he later died of unknown causes, but not before he had two Moorish pilots killed including the best pilot in all of India left to him by Vasco da Gama, in misplaced revenge for the death of his brother.

After burying their dead on the island the surviving Portuguese spent six days salvaging as much as they could from the wrecks before setting fire to the hulls. Under the new command of Pêro de Ataíde, the three remaining ships sailed back to India where they met Francisco D’Albuquerque and according to Ataíde handed over 17 pieces of artillery they had salvaged from the wrecks. Ataíde later succumbed to illness and died in early 1504 after his ship wrecked near Mozambique during his return journey to Lisbon. Shortly before he died, however, Ataíde wrote a five-page personal letter to Dom Manuel relating the events described above. This letter, the original of which is held in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo in Lisbon, represents the most complete first-hand account of what transpired with the Sodré squadron.

Dom Manuel I

Dom Manuel became the King of Portugal in October 1495 having succeeded his cousin and brother-in-law Dom João II, who died after failing to promote his illegitimate son Dom Jorge to the throne instead. Despite Manuel’s indirect accession to the throne and the resistance he faced to his ambition of adding new titles to the Portuguese crown through the discovery of foreign lands, he proved to be one of Portugal’s most important rulers and was known as Manuel the Fortunate. His (1495-1521) reign was marked by numerous significant events including reformation of the feudal system, publication of the Manueline Ordinances, reorganisation of the State’s legal, administrative and bureaucratic systems. He also encouraged architecture and oversaw the construction of major buildings, including the Convent of Christ in Tomar, Jerónimos Monastery and the Tower of Belém in Lisbon, which are all World Heritage Sites standing today.

However, more than any Monarch before or since, it was Dom Manuel who established Portugal as a global power based on its overseas expansion and maritime trade. Manuel’s reign was a highpoint during Portugal’s Golden Age of Discovery. It was marked by the discovery of the sea route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498, the discovery of Brazil in 1500 by Pedro Álvares Cabral and the creation of a powerful Viceroy system in India, which enabled Alfonso de Albuquerque to establish important trade monopolies in the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf and parts of the Far East. Before his elevation to the throne Manuel adopted the armillary sphere (a model of the celestial globe) as his personal emblem. The other iconic symbol he embraced was the cross of the Order of Christ. The cross of Christ, encircled by the words IИ HOC SIGИO VIИCES (Latin translation: in this sign you will conquer), began appearing on gold and silver coins especially commissioned by Manuel for overseas trade the year following da Gama’s momentous voyage to India. Both symbols perfectly reflected the expansionist policy that was at the core of Dom Manuel’s empire building made possible by sturdy Portuguese ships and their brave crews.

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama’s discovery of the sea route to India in 1498 has been described as one of the most important events recorded in the history of mankind. For Portugal, this daring and courageous exploit of seamanship and navigation gave this small Iberian country virtually total control of the rich spice trade with India and it opened up further explorations throughout the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf and the Far East. According to the British historian Sir John H. Plumb, the Portuguese “by the middle of the 16th century dominated more of the world and more of its trade than any other country.” To fully appreciate the lead, or “first-mover advantage”, da Gama gave the Portuguese over its seaborne rivals, almost 100 years passed before any Dutch or English ships ventured as far East as the three small naus under his command.

Already a noble, a cavalier of the Order of Santiago and a fidalgo of the royal household, da Gama’s reward upon his triumphal return to Lisbon in 1499 was to be given the hereditary rights and income from his place of birth Sines and the new titles Dom and the Admiral of the Indies. In 1502, four years after his discovery of the direct sea route to India, Dom Manuel called again upon da Gama to command an armada to India. The military objective of this 4th Portuguese armada was to avenge the earlier attacks against Cabral’s fleet of 1500 and the massacre of Portuguese factory workers in Calicut by the Zamorin. Da Gama’s armada of 20 ships, including the naus commanded by his maternal uncles Vicente and Brás Sodré, arrived off the coast of southwest India in August of 1502 and engaged in a number of brutally violent acts of piracy and warfare against Muslim ships and the city of Calicut, which earned da Gama a fearsome reputation for violence that continues to cause debate today.

After a long period out of favour with Dom Manuel, in part due to the irresponsible and costly actions of his uncles Vicente and Brás Sodré, da Gama made one last voyage to India at the bequest of Dom Manuel’s son João III who succeeded his father as King when he died in late 1521. Da Gama was named Viceroy of India by João, only the second Governor to be granted this prestigious title. He arrived in India in September 1524 but died three months later on Christmas Eve having contracted malaria – a common cause of death for those making this perilous voyage. As the hero of Os Lusiadas, Camões’ epic poem about the Portuguese voyages of discovery written in 1572 in the style of Homer’s Iliad, da Gama’s legend has continued to grow with the passing of time such that his position as one of the greatest Portuguese is forever assured.

Vicente Sodré

Vicente Sodré was an important and divisive figure in Vasco da Gama’s 1502-1503 armada to India. Vicente was a knight of the Order of Christ and of the royal household, and with his younger brother Brás were uncles to Vasco da Gama by way of their sister Isabel’s marriage to da Gama’s father Estêvão. Although established in Portugal since the late 14th century, the Sodrés actually descended from the English knight Frederick Sudley of Gloucestershire who originally came with the Earl of Cambridge to fight the Castilians in 1381 but remained in Portugal afterwards.

The senior Sodré’s importance in da Gama’s armada derived from the separate regimento he was given by Dom Manuel and the fact that he was to assume the role of Captain-Major if anything happened to his nephew. Dom Manuel’s regimento tasked Vicente to use his partially independent squadron of five ships to “make war against the ships of Meca” along the coast of Malabar and the entrance to the Red Sea following the return of da Gama and the main fleet of 15 ships to Portugal. In leaving behind Vicente’s smaller squadron to patrol the southwest Indian coast, Dom Manuel was looking to forcibly control and dominate the spice trade by the naval power of his technically superior ships armed with heavy guns. Vicente essentially ignored these instructions, however, with ultimately disastrous consequences for both the Crown and the Sodré brothers.

Instead of protecting the Portuguese factories at Cochin and Cannanur as ordered and promised, Vicente’s squadron abandoned their patrol and sailed away in search of rich trading ships to take as prizes. Abetted by his brother Brás, Vicente plundered a handful Muslim-owned vessels and then proceeded to kill all the crews and burn the ships. Their ruthless and murderous behaviour was matched only by their greed in keeping the best and largest quantity of stolen goods to themselves, which angered the other Captains in the squadron and fermented a poisonous atmosphere amongst the crews. The arrogance and irresponsibility of Vicente and Brás Sodré ultimately cost them their lives on the rocky shores of Al Hallaniyah island, along with a considerable cost to the fortunes of the Portuguese Crown and the reputation of Vasco da Gama.